Conversion factors are special fractions that contain problem-solving information. Why are they called conversion factors? “Conversion” means change, and conversion factors help you change the numbers and units in your problem. “Factors” are things you multiply with. So to use a conversion factor, you will multiply it by something.

For instance, if I am driving an average of 60 mph on the highway, I can use that rate as a conversion factor. I may use the fraction  , or I may flip it over to make

, or I may flip it over to make  . It all depends on what problem I want to solve.

. It all depends on what problem I want to solve.

After driving two hours, I have traveled:

miles so far.

miles so far.

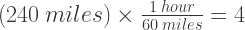

But if I am planning to go 240 more miles, and I need to know when I will arrive:

hours to go.

hours to go.

Any rate can be used as a conversion factor. You can recognize them by their form: this per that. Miles per hour, dollars per gallon, cm per meter, and many, many more.

Of course, you will need to use the rate that is relevant to the problem you are trying to solve. If I were trying to figure out how far a tank of gas would take me, it wouldn’t be any help to know that an M1A1 Abrams tank gets 1/3 mile per gallon. I won’t be driving one of those.

Using Conversion Factors Is Like Multiplying by One

If I am driving 65 mph on the interstate highway, then driving for one hour is exactly the same as driving 65 miles, and:

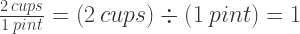

This may be easier to see if you think of kitchen measurements. Two cups of sour cream are exactly the same as one pint of sour cream, so:

If I want to find out how many cups are in 3 pints of sour cream, I can multiply by the conversion factor:

Multiplying by one does not change the original number. In the same way, multiplying by a conversion factor does not change the original amount of stuff. It only changes the units that you measure the stuff in. When I multiplied 3 pints times the conversion factor, I did not change how much sour cream I had, only the way I was measuring it.

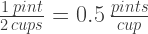

Conversion Factors Can Always Be Flipped Over

If there are  , then there must also be

, then there must also be  .

.

If I draw house plans at a scale of  , that is the same as saying

, that is the same as saying  .

.

If there are  , then there is

, then there is  .

.

Or if an airplane is burning fuel at  , then the pilot has only 1/8 hour left to fly for every gallon left in his tank.

, then the pilot has only 1/8 hour left to fly for every gallon left in his tank.

This is true for all conversion factors, and it is an important part of what makes them so useful in solving problems. You can choose whichever form of the conversion factor seems most helpful in the problem at hand.

How can you know which form will help you solve the problem? Look at the units you have, and think about the units you need to end up with. In the sour cream measurement above, I started with pints and I wanted to end up with cups. That meant I needed a conversion factor with cups on top (so I would end up with that unit) and pints on bottom (to cancel out).

You Can String Conversion Factors Together

String several conversion factors together to solve more complicated problems. Just as numbers cancel out when the same number is on the top and bottom of a fraction (2/2 = 2 ÷ 2 = 1), so do units cancel out if you have the same unit in the numerator and denominator. In the following example, quarts/quarts = 1.

How many cups of milk are there in a gallon jug?

As you write out your string of factors, you will want to draw a line through each unit as it cancels out, and then whatever is left will be the units of your answer. Notice that only the units cancel — not the numbers. Even after I canceled out the quarts, the 4 was still part of my calculation.

Let’s Try One More

The true power of conversion factors is their ability to change one piece of information into something that at first glance seems to be unrelated to the number with which you started.

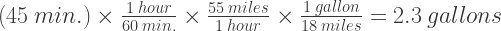

Suppose I drove for 45 minutes at 55 mph in a pickup truck that gets 18 miles to the gallon, and I wanted to know how much gas I used. To find out, I start with a plain number that I know (in this case, the 45 miles) and use conversion factors to cancel out units until I get the units I want for my answer (gallons of gas). How can I change minutes into gallons? I need a string of conversion factors:

How Old Are You, Anyway?

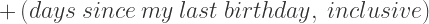

If you want to find your exact age in nanoseconds, you need to know the exact moment at which you were born. But for a rough estimate, just knowing your birthday will do. First, find out how many days you have lived:

Once you know how many days you have lived, you can use conversion factors to find out how many nanoseconds that would be. You know how many hours are in a day, minutes in an hour, and seconds in a minute. And just in case you weren’t quite sure:

Have fun playing around with conversion factors. You will be surprised how many problems these mathematical wonders can solve.

[Note: This article is adapted from my out-of-print book, Master the Math Monsters.]