The ability to solve word problems ranks high on any math teacher’s list of goals. How can I teach my students to reason their way through math problems? I must help my students develop the ability to translate “real world” situations into mathematical language.

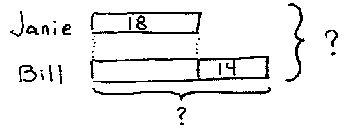

In a previous post, I analyzed two problem-solving tools we can teach our students: algebra and bar diagrams. These tools help our students organize the information in a word problem and translate it into a mathematical calculation.

Now I want to demonstrate these problem-solving tools in action with a series of 2nd grade problems, based on the Singapore Primary Math series, level 2A.

Now I want to demonstrate these problem-solving tools in action with a series of 2nd grade problems, based on the Singapore Primary Math series, level 2A. For your reading pleasure, I have translated the problems into the universe of one of our family’s favorite read-aloud books, Mr. Popper’s Penguins.

UPDATE: Problems have been genericized to avoid copyright issues.

Continue reading Penguin Math: Elementary Problem Solving 2nd Grade