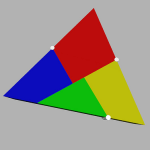

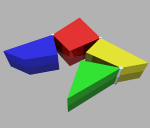

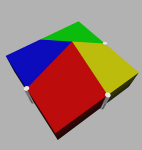

I love using rectangles as a model for multiplication. In this video, Mike & son offer a pithy demonstration of WHY a negative number times a negative number has to come out positive:

How To Master Quadratic Equations

Feature photo above by Junya Ogura via Flickr (CC BY 2.0).

A couple of weeks ago, James Tanton launched a wonderful resource: a free online course devoted to quadratic equations. (And he promises more topics to come.)

Kitten and I have been working through the lessons, and she loves it!

We’re skimming through pre-algebra in our regular lessons, but she has enjoyed playing around with simple algebra since she was in kindergarten. She has a strong track record of thinking her way through math problems, and earlier this year she invented her own method for solving systems of equations with two unknowns.

I would guess her background is approximately equal to an above-average Algebra 1 student near the end of the first semester.

After few lessons of Tanton’s course, she proved — within the limits of experimental error — that a catenary (the curve formed by a hanging chain) cannot be described by a quadratic equation. Last Friday, she easily solved the following equations:

and:

and (though it took a bit more thought):

We’ve spent less than half an hour a day on the course, as a supplement to our AoPS Pre-Algebra textbook. We watch each video together, pausing occasionally so she can try her hand at an equation before listening to Tanton’s explanation. Then (usually the next day) she reads the lesson and does the exercises on her own.

So far, she hasn’t needed the answers in the Companion Guide to Quadratics, but she did use the “Dots on a Circle” activity — and knowing that she has the answers available helps her feel more independent.

How to Recognize a Successful Homeschool Math Program

After teaching co-op math classes for several years, I’ve become known as the local math maven. Upon meeting one of my children, fellow homeschoolers often say, “Oh, you’re Denise’s son/daughter? You must be really good at math.”

The kids do their best to smile politely — and not to roll their eyes until the other person has turned away.

I hear similar comments after teaching a math workshop: “Wow, your kids must love math!” But my children are individuals, each with his or her own interests. A couple of them enjoy an occasional geometry or logic puzzle, but they never voluntarily sit down to slog through a math workbook page.

In fact, one daughter expressed the depth of her youthful perfectionist angst by scribbling all over the cover of her Miquon math workbook:

- “I hate math! Hate, hate, hate-hate-HATE MATH!!!”

Translation: “If I can’t do it flawlessly the first time, then I don’t want to do it at all.”

Continue reading How to Recognize a Successful Homeschool Math Program

2013 Mathematics Game

feature photo above by Alan Klim via flickr

New Year’s Day

Now is the accepted time to make your regular annual good resolutions. Next week you can begin paving hell with them as usual.

Yesterday, everybody smoked his last cigar, took his last drink, and swore his last oath. Today, we are a pious and exemplary community. Thirty days from now, we shall have cast our reformation to the winds and gone to cutting our ancient shortcomings considerably shorter than ever. We shall also reflect pleasantly upon how we did the same old thing last year about this time.

However, go in, community. New Year’s is a harmless annual institution, of no particular use to anybody save as a scapegoat for promiscuous drunks, and friendly calls, and humbug resolutions, and we wish you to enjoy it with a looseness suited to the greatness of the occasion.

— Mark Twain

Letter to Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, Jan. 1863

For many homeschoolers, January is the time to assess our progress and make a few New Semester’s Resolutions. This year, we resolve to challenge ourselves to more math puzzles. Would you like to join us? Pump up your mental muscles with the 2013 Mathematics Game!

Who Killed Professor X?

What a Fun Book!

Who Killed Professor X? is a work of fiction based on actual incidents, and its heroes are real people who left their mark on the history of mathematics. The murder takes place in Paris in 1900, and the suspects are the greatest mathematicians of all time. Each suspect’s statement to the police leads to a mathematical problem, the solution of which requires some knowledge of secondary-school mathematics. But you don’t have to solve the puzzles in order to enjoy the book.

Fourteen pages of endnote biographies explain which parts of the mystery are true, which details are fictional, and which are both (true incidents slightly modified for the sake of the story).

My daughter Kitten, voracious as always, devoured it in one sitting — and even though she hasn’t studied high school geometry yet, she was able to work a couple of the problems.

Rate × Time = Distance Problems

I love how Richard Rusczyk explains math problems. It’s a new school year, and that means it’s time for new MathCounts Mini videos. Woohoo!

- Download the activity sheet with warm-up and follow-up problems.

Build Mathematical Skills by Delaying Arithmetic, Part 4

To my fellow homeschoolers,

While Benezet originally sought to build his students’ reasoning powers by delaying formal arithmetic until seventh grade, pressure from “the deeply rooted prejudices of the educated portion of our citizens” forced a compromise. Students began to learn the traditional methods of arithmetic in sixth grade, but still the teachers focused as much as possible on mental math and the development of thinking strategies.

Notice how waiting until the children were developmentally ready made the work more efficient. Benezet’s students studied arithmetic for only 20-30 minutes per day. In a similar modern-day experiment, Daniel Greenberg of Sudbury School discovered the same thing: Students who are ready to learn can master arithmetic quickly!

Grade VI

[20 to 25 minutes a day]

At this grade formal work in arithmetic begins. Strayer-Upton Arithmetic, book III, is used as a basis.

[Note: Essentials of Arithmetic by George Wentworth and David Eugene Smith is available free and would probably work as a substitute.]

The processes of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are taught.

Care is taken to avoid purely mechanical drill. Children are made to understand the reason for the processes which they use. This is especially true in the case of subtraction.

Problems involving long numbers which would confuse them are avoided. Accuracy is insisted upon from the outset at the expense of speed or the covering of ground, and where possible the processes are mental rather than written.

Before starting on a problem in any one of these four fundamental processes, the children are asked to estimate or guess about what the answer will be and they check their final result by this preliminary figure. The teacher is careful not to let the teaching of arithmetic degenerate into mechanical manipulation without thought.

Fractions and mixed numbers are taught in this grade. Again care is taken not to confuse the thought of the children by giving them problems which are too involved and complicated.

Multiplication tables and tables of denominate numbers, hitherto learned, are reviewed.

— L. P. Benezet

The Teaching of Arithmetic II: The Story of an experiment

Continue reading Build Mathematical Skills by Delaying Arithmetic, Part 4

Multiplication Challenge

Can you explain why the multiplication method in the following video works? How about your upper-elementary or middle school students — can they explain it to you?

Pause the video at 4:30, before he gives the interpretation himself. After you have decided how you would explain it, hit “play” and listen to his explanation.

How Long is 10! Seconds?

A fun exploration for upper elementary or middle school students, from Numberphile:

Thinking (and Teaching) like a Mathematician

Most people think that mathematics means working with numbers and that being “good at math” means being able to do (only slower) what any $10 calculator can do. But then, most people think all sorts of silly things, right? That’s what makes “man on the street” interviews so funny.

Numbers are definitely part of math — but only part, and not even the biggest part. And being “good at math” means much more than being able to work with numbers. It means making connections, thinking creatively, seeing familiar things in new ways, asking “Why?” and “What if?” and “Are you sure?”

It means trying something and being willing to fail, then going back and trying something else. Even if your first try succeeded — or maybe, especially if your first try succeeded. Just knowing one way to do something is not, for a mathematician, the same as understanding that something. But the more different ways you know to figure it out, the closer you are to understanding it.

Mathematics is not just memorizing and following rules. If we want to teach real mathematics, we teachers need to learn to think like mathematicians. We need to see math as a mental game, playing with ideas. James Tanton explains:

Continue reading Thinking (and Teaching) like a Mathematician