[Dragon photo above by monkeywingand treasure chest by Tom Praison via flickr.]

Over the years, some of my favorite blog posts have been the Word Problems from Literature, where I make up a story problem set in the world of one of our family’s favorite books and then show how to solve it with bar model diagrams. The following was my first bar diagram post, and I spent an inordinate amount of time trying to decide whether “one fourth was” or “one fourth were.” I’m still not sure I chose right.

I hope you enjoy this “Throw-back Thursday” blast from the Let’s Play Math! blog archives:

Cimorene spent an afternoon cleaning and organizing the dragon’s treasure. One fourth of the items she sorted was jewelry. 60% of the remainder were potions, and the rest were magic swords. If there were 48 magic swords, how many pieces of treasure did she sort in all?

[Problem set in the world of Patricia Wrede’s Enchanted Forest Chronicles. Modified from a story problem in Singapore Primary Math 6B. Think about how you would solve it before reading further.]

How can we teach our students to solve complex, multi-step story problems? Depending on how one counts, the above problem would take four or five steps to solve, and it is relatively easy for a Singapore math word problem. One might approach it with algebra, writing an equation like:

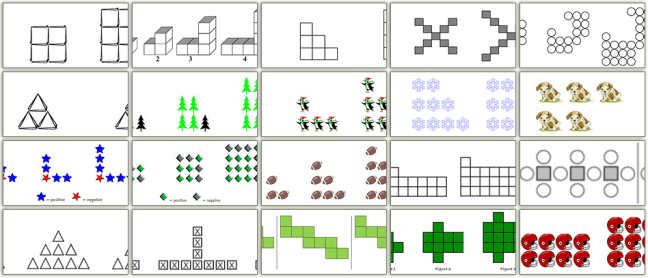

… or something of that sort. But this problem is for students who have not learned algebra yet. Instead, Singapore math teaches students to draw pictures (called bar models or math models or bar diagrams) that make the solution appear almost like magic. It is a trick well worth learning, no matter what math program you use …

[Click here to go read Solving Complex Story Problems.]

Update: My New Book

You can help prevent math anxiety by giving your children the mental tools they need to conquer the toughest story problems.

Read Cimorene’s story and many more in Word Problems from Literature: An Introduction to Bar Model Diagrams—now available at all your favorite online bookstores!

And there’s a Student Workbook, too.