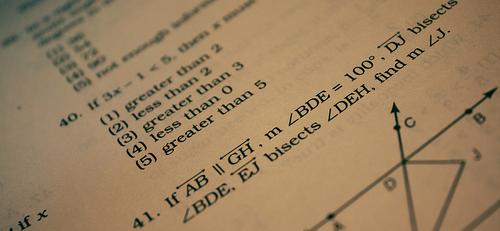

[Photo by pfala.]

Thanks to John Cook’s article about factorials in the recent Mathematics and Multimedia Carnival, we’re adding new rules to the 2010 Mathematics Game.

Let’s play with multifactorials!

[Photo by pfala.]

Thanks to John Cook’s article about factorials in the recent Mathematics and Multimedia Carnival, we’re adding new rules to the 2010 Mathematics Game.

Let’s play with multifactorials!

Symbolic Logic Part I was published in 1896. When Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) died two years later, Part II was lost. Because they couldn’t find the manuscript, many people doubted that he ever wrote Part II. But almost eighty years after his death, portions of Part II were recovered and finally published. The following puzzles are from the combined volume, Lewis Carroll’s Symbolic Logic, edited by William Warren Bartley, III.

These puzzles are called soriteses or polysyllogisms. Carroll began with a series of “if this, then that” statements. He rewrote them to make them more confusing, and then he mixed up the order to create a challenging puzzle.

Given each set of premises, what conclusion can you reach?

Mondays come every week. Bleh! Here are some puzzles I found this weekend, to brighten up your day…

[Photo by Ella’s Dad.]

Throughout history, around the world, people in every culture have enjoyed playing games of chance. Strangely, mathematicians did not begin to study chance and probability until the 17th century.

Students headed into finals week need to blow off some steam, so let’s have a little fun with calculus. Hey, Niner, does this look familiar?…

[Photo by pfala.]

Did you know that playing games is one of the Top 10 Ways To Improve Your Brain Fitness? So slip into your workout clothes and pump up those mental muscles with the 2010 Mathematics Game!

Use the digits in the year 2010 to write mathematical expressions for the counting numbers 1 through 100.

- All four digits must be used in each expression. You may not use any other numbers except 2, 0, 1, and 0.

- You may use the arithmetic operations +, -, x, ÷, sqrt (square root), ^ (raise to a power), and ! (factorial). You may also use parentheses, brackets, or other grouping symbols.

- You may use a decimal point to create numbers such as .1, .02, etc.

- Multi-digit numbers such as 20 or 102 may be used, but preference is given to solutions that avoid them.

Bonus Rule

You may use the overhead-bar (vinculum), dots, or brackets to mark a repeating decimal.[Note to teachers: This rule is not part of the Math Forum guidelines. It makes a significant difference in the number of possible solutions, however, and it should not be too difficult for high school students or advanced middle schoolers.]

[Photo by *Irish.]

In my post Elementary Problem Solving: The Tools, I introduced word algebra as a way to help students think their way through a story problem. In the next two posts, I showed how the tool worked with simple word problems.

Now, before I move on to focus exclusively on bar diagrams, I would like to show how word algebra can help a student solve a typical first-year algebra puzzle.

A homeschooling friend who avoided algebra in high school, trying to help her son cope with a subject she never understood, posted: “Help! Our answer is different from the book’s.” Here is the homework problem:

Josh earned $72 less than his sister who earned $93 more than her mom. If they earned a total of $504, how much did Josh earn?

[I couldn’t find a good picture illustrating “division.” Niner came to my rescue and took this photo of her breakfast.]

I found an interesting question at Mathematics Education Research Blog. In the spirit of Liping Ma’s Knowing and Teaching Elementary Mathematics, Finnish researchers gave this problem to high school students and pre-service teachers:

We know that:

How could you use this relationship (without using long-division) to discover the answer to:

[No calculators allowed!]

The Finnish researchers concluded that “division seems not to be fully understood.” No surprise there!

Check out the pdf report for detailed analysis.

[Photo by Aaron Escobar. This post is a revision and update of How to Solve Math Problems from October, 2007.]

What can you do when you are stumped by a math problem? Not just any old homework exercise, but one of those tricky word problems that can so easily confuse anyone?

The difference between an “exercise” and a “problem” will vary from one person to another, even within a single class. Even so, this easy to remember, 4-step approach can help students at any grade level. In my math classes, I give each child a copy to keep handy:

[Note: Page 1 is the best for quick reference, especially with elementary to middle school children. Page 2 lists the steps in more detail, for the teacher or for older students.]

Considering how many fools can calculate, it is surprising that it should be thought either a difficult or a tedious task for any other fool to learn how to master the same tricks… Being myself a remarkably stupid fellow, I have had to unteach myself the difficulties, and now beg to present to my fellow fools the parts that are not hard. Master these thoroughly, and the rest will follow. What one fool can do, another can.

For years, I have recommended Calculus Made Easy as summer reading (and future reference) for high school or college students headed into a calculus course — and for the parents of those students, who may have studied calculus in ages past and now need to dredge out the dust bunnies of memory so they can help with homework.

The original book (second edition) is now out of copyright and available for free online:

[Hat tip to Sam and Michael for finding the Scribd version, which set me off searching for a clearer copy.]